Art must go on(line)

From Peter Struycken to Harm van den Dorpel, our online exhibition Art must go on(line) with artworks from the ING Collection, is about the successful marriage between art and digital technology and how they redefine each other in new and exciting ways.

Art and technology have a rich history of working together and cross-pollination, starting back in the 1960s when artists began exploring the possibility of using computers to make art. That this was sparked off in the turbulent sixties is no surprise. It was a time when the art community’s interest in new materials revolutionised the role and meaning of art. This radical shift and the infinity of new possibilities paved the way for computer art.

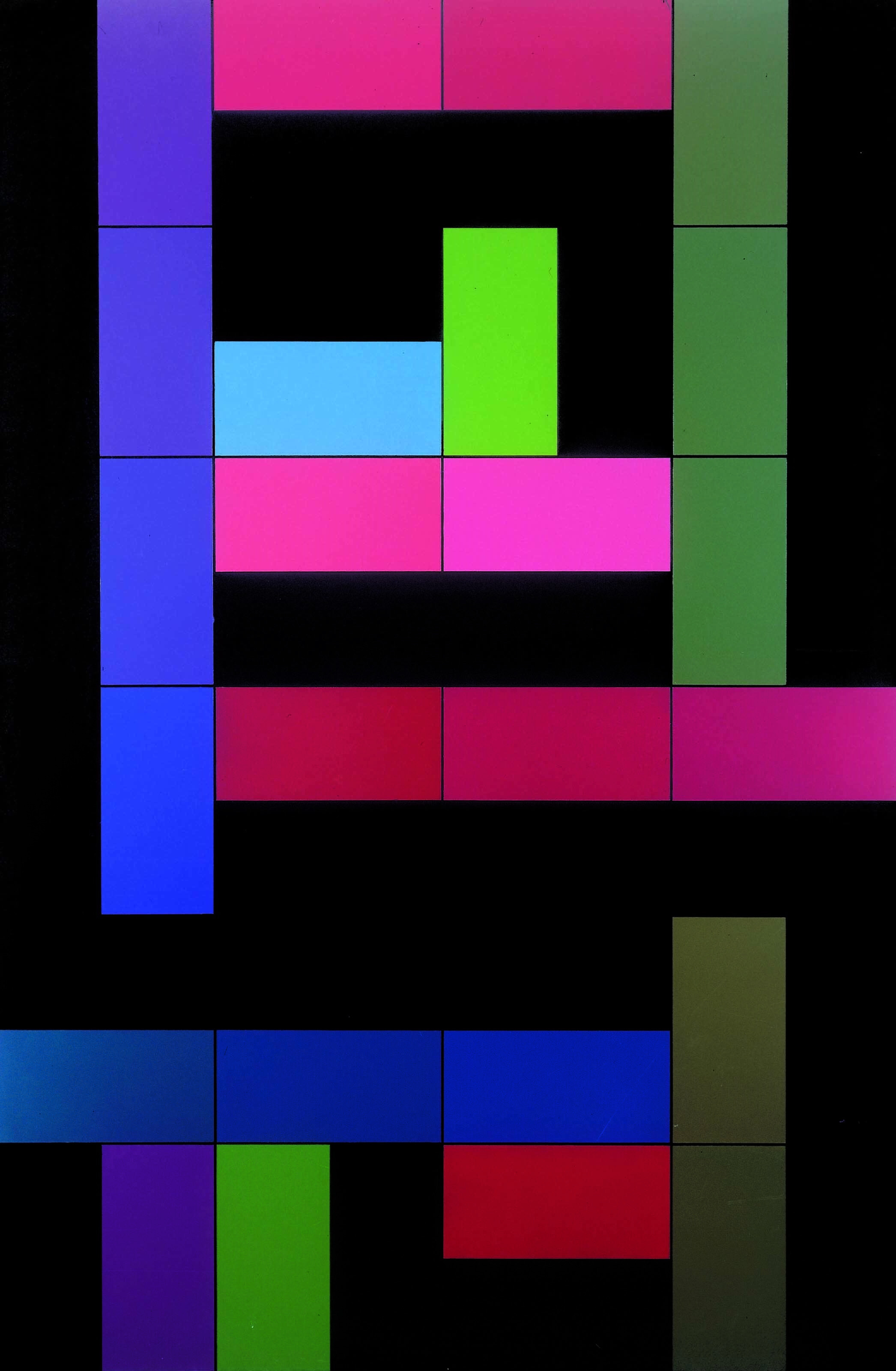

Cluster No. 14 (1975) by Peter Struycken

Peter Struycken (1939)

Peter Struycken was one of the first in the Netherlands to use computers to create art. Way ahead of his time, he discovered this possibility long before the personal computer had made its way into our homes.

By the end of the 1960s, Struycken was using computers to calculate the underlying structure of his artworks. While other artists at that time mainly stuck to expressing their emotions and giving their own personal interpretation of reality, Struycken went in search of fixed structures and the laws of shape and colour. Everything needed to be logical, controllable and consistent. Cluster No. 14 is part of a series of paintings made with the help of the Cluster computer program that contains 24 elements, each consisting of a black and a coloured half. According to particular rules, the elements were transferred to this painting.

The 1990s saw the birth of internet art, also known as ‘net art’: original artworks made on or for the internet. It took a while for museums to warm to this new movement, not in the least because of the difficulty of exhibiting this new media. Today, as software and hardware become increasingly available and affordable, digital exhibitions are becoming more popular in museums. Digital art now occupies a prominent place in the traditional art world, and artists like Rafaël Rozendaal, Peter Kogler and Tabor Robak belong to the absolute top.

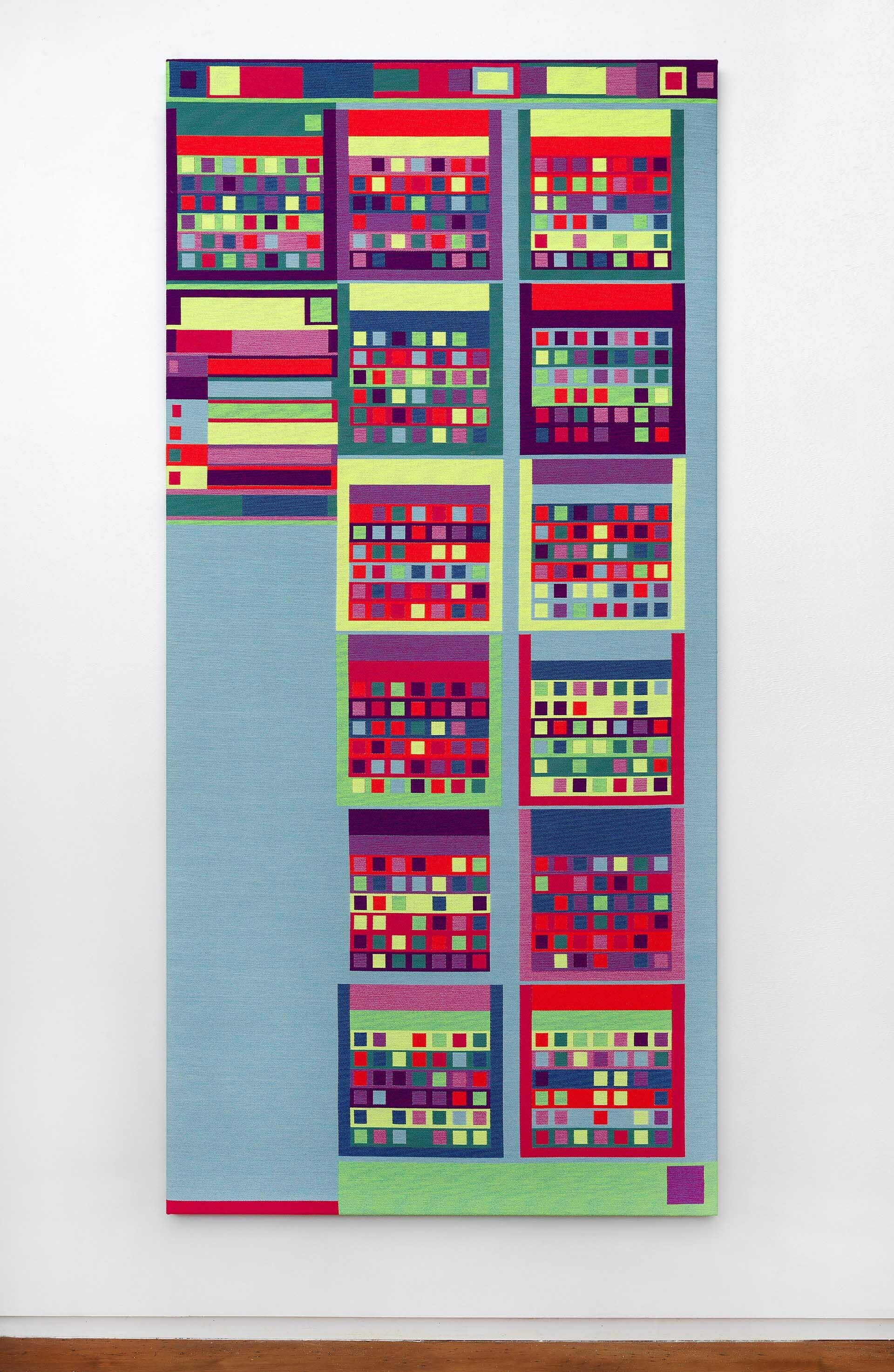

Abstract Browsing 16 10 01 (Google docs) (1980) by Rafaël Rozendaal

Rafaël Rozendaal (1980)

Dutch-Brazilian Rafaël Rozendaal was one of the first artists to sell websites as objects of art. Recognised as a pioneer in internet art, he started selling domain names to create his art as early as in 2001. His interactive websites are simple yet colourful, with algorithms that keep things changing before our very eyes. With the internet as his canvas, Rozendaal explores the interaction and connection between art and the internet.

It was in 2014 that Rozendaal developed his Abstract Browsing plug-in. Its coding transforms websites into brightly coloured geometric elements: the narrative of the internet makes way for an abstract composition that reveals the underlying structure of individual websites. He turns only a handful of the thousands of websites he visits with this plug-in into actual artworks by making tapestries out of these images. If you feel like experimenting, his free browser plug-in (http://www.abstractbrowsing.net/) reduces all web content to blocks of colour, as seen here.

Rafaël Rozendaal

Northstar Special Edition (1986) by Tabor Robak

Tabor Robak (1986)

The Michelangelo of digital art, or ‘Pixelangelo’, Tabor Robak has always enjoyed a nice walk in the wood.

A 15 metre-wide digital artwork at ING’s head office, Northstar simulates an infinite walk in nature. Robak sees the natural world as the perfect antidote to the bubbling anxiety of modern life. Ironically, he decided to capture this feeling in an endless virtual experience.

Billow, 2000 (2020) by Daniel Canogar

Daniel Canogar (1964)

Daniel Canogar created Billow in the hopes of better understanding the ebb and flow of our digital times.

Billow consists of a wavy digital LED screen with abstract images based on real-time data from online search engines and trending news articles and YouTube videos. Its colours change depending on the popularity of an item or search term: the ‘hotter’ it becomes, the warmer the colour.

Swiped Horizon - Stormy Sky (2020) by Noor Nuyten

Noor Nuyten (1986)

In her work, Dutch artist Noor Nuyten takes a critical yet playful look at the rational structures that frame our lives.

For Swiped Horizon – Stormy Sky, Nuyten embraced her inner child and swiped navy blue paint onto photo paper with her fingers. This motion is a reference to our relationship with our phones. Traces of her fingerprints can be seen upon closer inspection.

Odd Motives (2021) by Harm van den Dorpel

Harm van den Dorpel (1981)

Harm van den Dorpel has a well-constructed method for doing art – but it might not be what you’d expect. He’s a bit of a mad scientist!

In fact, he built his own Mutant Garden software to produce Odd Motives. The program breeds unpredictable combinations of shapes and colours – mutations – which Van den Dorpel then selects and enhances to emphasise interesting traits.

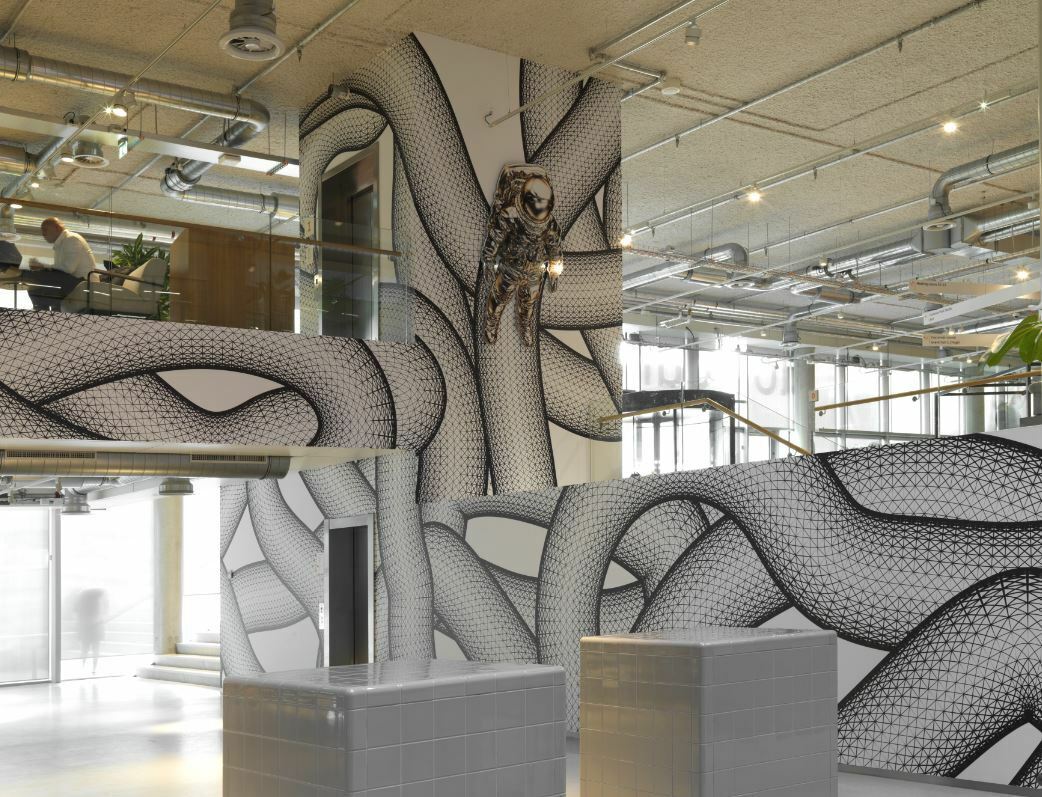

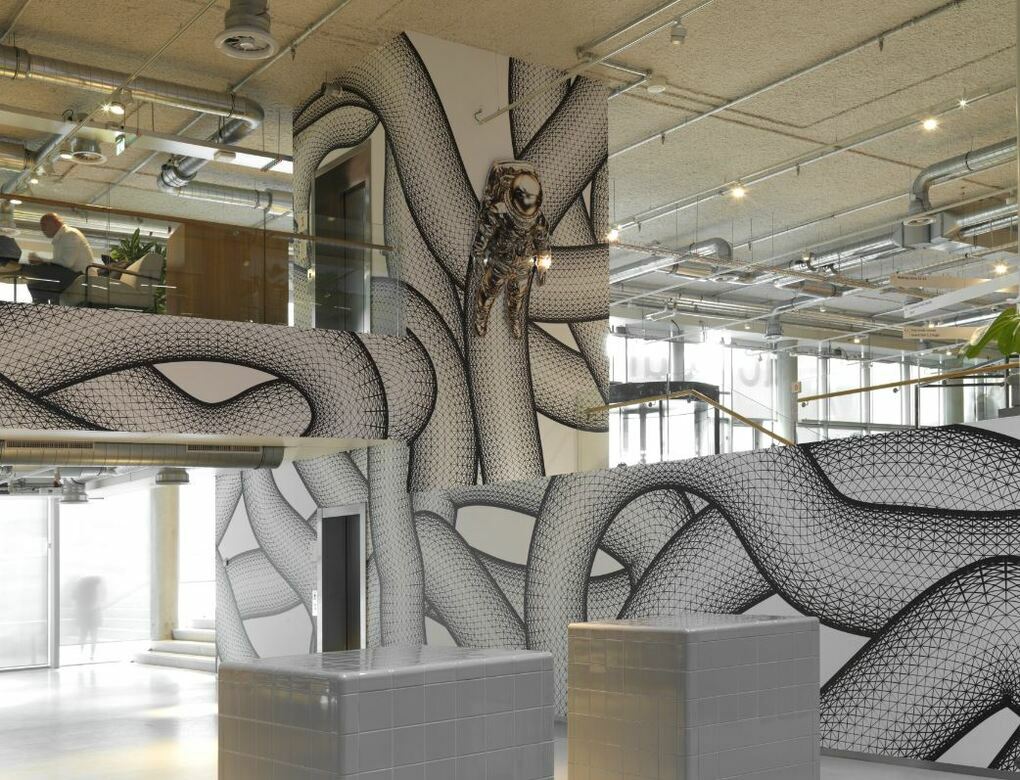

Untitled (2019) by Peter Kogler

Peter Kogler (1959)

If you’ve ever been to ING’s head office in Amsterdam, you’re already familiar with the work of Peter Kogler. It’s the first thing you see when you enter the building. A pioneer in computer-generated art, Kogler was commissioned to create this immersive art installation that connects several floors with an impressive pattern of lines. It’s a symbol of connectivity.

While more and more artists are creating digital art, NFTs have made it possible to buy and sell these works on a large scale. NFTs (non-fungible tokens) act as a non-duplicable digital certificate of ownership, just like how traditional prints are issued in limited edition with a certificate of authenticity. So you could say that the concept of NFTs already existed. What’s revolutionary is the tech behind them. Secured by blockchain digital encryption technology, NFTs make it possible to take the artwork you bought wherever you go – all you need is an internet connection.

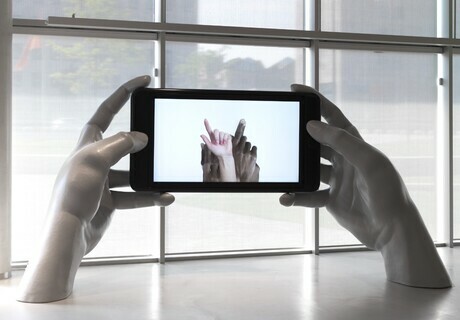

Still from The Absence of Presence (2015) by Dragos Alexandrescu

ING's first NFT: The Absence of Presence by Dragos Alexandrescu

In 2019 ING acquired its first NFT: The Absence of Presence by Romanian artist Dragos Alexandrescu. This artwork shows the impact of digitalisation on human interaction. In the video we hear two people having a conversation. At the same time, we see a choreography of hand gestures used by people to operate touchscreen devices. Seen as a form of expressing our emotions by using technology, the video poses its own alternative questions and reflects on our absence of physical interaction and its consequences for our social behaviour.

Touch-ING (2019) by Constant Dullaart

Constant Dullaart (1979)

Another blockchain early bird is Dutch artist Constant Dullaart, who sold his first NFT in 2016. Fascinated by the nexus between art and technology in the digital age, he has used his artistic abilities to explore the ways in which the internet informs and manipulates our relationship with art and images. Especially for the ING Collection, Dullaart created Touch-ING: an enormous telephone screen showing the hand gestures that we use on our tablets. When you touch the screen, a map will appear with all the works of art that are present in the ING head office Cedar.

Touch-ING by Constant Dullaart

As the internet became a staple of daily life, it was only going to be a matter of time before post-internet art was born. While internet artists used the internet primarily as a medium, today’s post-internet artists create work that reflects on the internet’s role in society. Although influenced by the web, post-internet art doesn’t necessarily have to be made online. Post-internet artists also use tangible offline art to reflect on our growing use of the internet and its impact on our world.

Refuge (Ganvie) (2014) by Markus Selg

Markus Selg (1974)

What’s real and what isn’t? These are the big questions that German artist Markus Selg asks in his work. Through sculpture, collage, installation and film, he explores what it means to live in a world where so many images exist only as bits and bytes. Markus Selg sees the world as a place where technology and spirituality exist side by side, sometimes quite literally.

This installation shows images filmed by Selg during his travels in Benin, West Africa. While there, he became interested in voodoo. Images of flying bats, a red twinkling screen and a video of the lake village of Ganvie filmed from a canoe create a dialogue in this work.

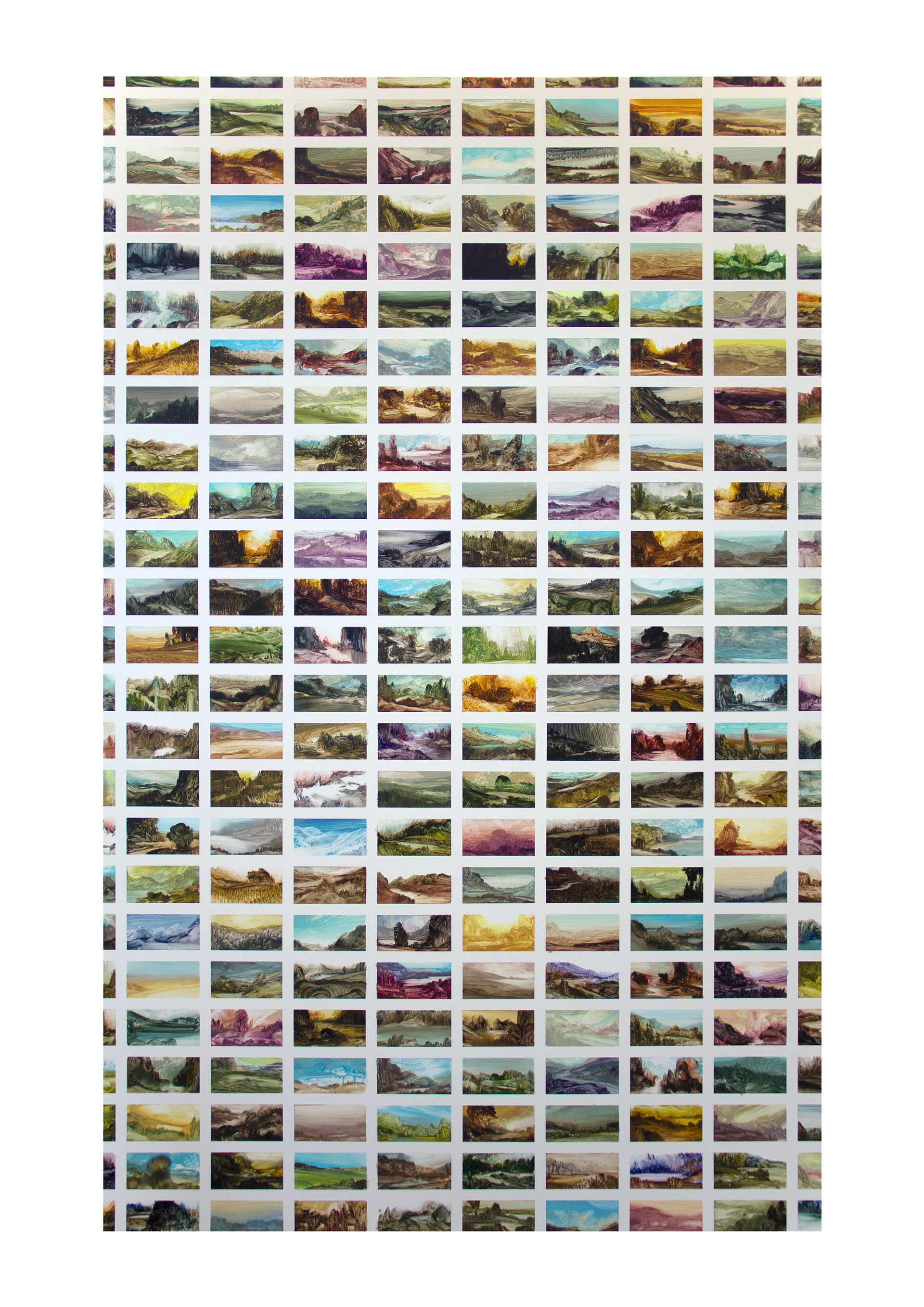

Untitled (2016) by Stefan Peters

Stefan Peters (1978)

Have we as human beings reached a point that we recognise something as fake but can relate to it all the same?

Stefan Peters finds photographic landscape images from all over the world in Google Earth and then alters them through painting. Often, a sculptural staged foreground is combined with a painted background to create a sense of infinite depth. We can see that the images have been manipulated, but it’s difficult not to be intrigued.

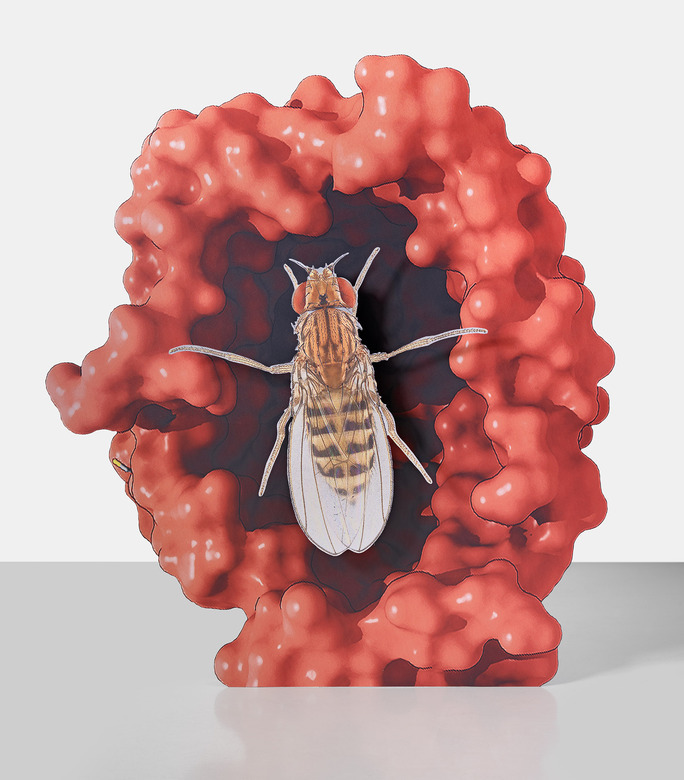

Approximation (5dl5.0 chimera surface ligand, fruit fly) (2017) by Katja Novitskova

Katja Novitskova (1984)

Katja Novitskova is concerned with how online images actively redefine our understanding of the world and our place in it.

In this work, Novitskova has cut and pasted an enlarged image of a fruit fly and a microscope image of a poison molecule suspended in space – to very confusing effect. Just like with the fruit fly trying to work out its alien surroundings, the world as we know it is no longer recognisable.

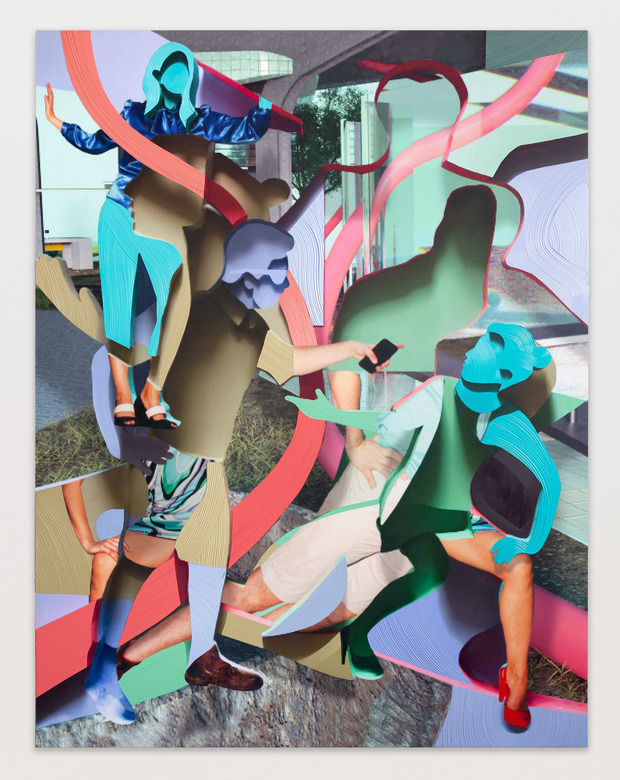

Behavioral Surplus Capture (2019) by Pieter Schoolwerth

Pieter Schoolwerth (1970)

Pieter Schoolwerth enjoys playing with multiple dimensions in his work. It helps him to keep grounded.

With Behavioral Surplus Capture, Schoolwerth moves beyond the standard two-dimensional image of mankind in paintings by connecting figures in many different ways. He takes analogue photos and digitally shapes them into three-dimensional works of art, showing that behind all digital networks there is a physical, material base.

Art @ the Office

Discover how some of the artworks in this exhibition are displayed at the ING offices

Thank you

We hope you’ve enjoyed this exhibition. We really appreciate this opportunity to share our art – both offline and online – with you. The ING Collection stands for quality, experimentation and innovation. It’s a reflection of topics and themes that are relevant in today’s society and to ING.